by Dennis Berkla

On July 25th in 1879 a remarkable discovery made front page news in the northern foothills of California’s Sacramento Valley. Within days the story was carried by newspapers from Redding to Sacramento, yet the record of this find soon faded to obscurity. Here is the article as it first appeared in the Oroville Mercury:

“A Relic of the Past”

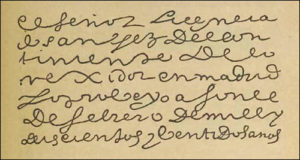

While chopping up an oak tree, which they had felled for the purpose of obtaining lumber to construct a cabin, James Reynolds and Joe McCarty, two miners working on Middle Fork of Feather river, last Thursday, found in a cavity in the interior of the tree a piece of parchment, 8×14 inches, both sides of which were covered with hieroglyphics, as they thought, excepting four figures, viz: “1542.” Naturally presuming it to be something of a curiosity, the gentlemen very properly decided to preserve the parchment, which they did until Monday of this week, when a San Francisco man, who was hunting in that section stopped at their camp and upon being shown the document offered $50 for it. The offer was accepted. Tuesday night the purchaser, who proved to be F.M. Castronjo, of Madrid, Spain, reached this city, en route to the Bay. We ran across him while in quest of items with this result: He said the characters on the parchment were Spanish letters; that he, being a well-educated Spaniard, had experienced no difficulty in deciphering the writing, and informed us that it was a condensed history of the wanderings, trials and tribulations of three men named Emanuel Sagosta, José Gareljos and Sebastian Murilo, deserters from the command of Hernando de Soto; that they were, at the time of writing, the sole survivors of a party of thirteen who ran away from the expedition on the 24th of November, 1539, and that this letter was written and put in a knothole in the oak on the 29th day of August, 1542: that the party were discouraged at the prospect of dying in the wilderness and had no idea as to whither their steps were leading them. He kindly permitted us to look at the parchment which was of a dark cream color, the writing thereon being easily perceived by the naked eye, its color being that of a faded blue. Prior to leaving this city, Mr. Castronjo had the article securely sealed up in a tin can to keep the air from it and intends disposing of it to the National Historical Society of Spain. In response to our inquiry as to how much the tree had grown in that time, he said the miners told him that the outer edge of the cavity was about five inches within the tree, which had grown over and completely closed the hole.

If the parchment was genuine, it would document a 16th century transcontinental journey in excess of 3,000 miles, presumably on foot, and make Hernan de Soto’s men the first Spaniards to enter the interior of Alta California. Unfortunately, no other “eyewitness” reports verify either the existence of this document or that it was ever seen again. Without that evidence, the newspaper report loses much of its credibility, for frontier journalists are known to have published similar articles comprised of little more than historical fantasy. But skepticism must not preclude investigation.

What is at issue is the validity of the reported desertion and subsequent journey. Without the document itself, the only alternative is to travel back in history surveying pertinent and verified records that offer some element of evidence supporting the Mercury’s assertion. The first test IS to reconcile the reference to Hernan de Soto’s expedition and the events preceding November 24th, 1539—the date of the alleged desertion.

As Governor General, Hernan de Soto had personally financed the Florida expedition using nearly all of his proceeds from the plunder of Peru. His gamble was that the fortune would return, only this time with the vast land grants and political power his new title conferred. When he arrived at the bay of Espiritu Santo in Florida, his armed expeditionary force of nearly one thousand was prepared to expropriate yet another rich civilization.

As Governor General, Hernan de Soto had personally financed the Florida expedition using nearly all of his proceeds from the plunder of Peru. His gamble was that the fortune would return, only this time with the vast land grants and political power his new title conferred. When he arrived at the bay of Espiritu Santo in Florida, his armed expeditionary force of nearly one thousand was prepared to expropriate yet another rich civilization.

De Soto had previously learned the value of maintaining peaceful relations with the natives with an accord, valuable information could be acquired so after seizing the local village he began sending peace envoys to its chief. His overtures were rejected however, and survivors of that expedition later recalled this event as their first in a series of grim revelations:

Here it was that he first came upon the traces of his predecessor, Pamphilo de Narvaez, and unfortunately, they were of a cruel character. Narvaez in his expedition to Florida had been bravely opposed by the cacique of this village, whose name was Hirrihigua. He succeeded, at length, in winning his friendship, and a treaty was formed between them. Subsequently, however, Narvaez became enraged at the cacique for some unknown reason, and in a transport of passion had ordered his nose to be cut off, and his mother to be torn to pieces by dogs.

Though aware that Narvaez’ expedition had ended in disaster, with all but four of his men perishing, de Soto also saw that his ships would have to remain in the bay of Espiritu Santo until another harbor could be found. Therefore, he made continuous efforts to overcome the chief’s enduring hatred of Spaniards. He sent gifts by way of the Indians that his men had captured, but it was to no avail. As Garcilaso de la Vega later recorded, de Soto could not gain sufficient confidence to obtain even a dialogue with the embittered cacique: “’I want none of their speeches nor promises,’ said he, bitterly, ‘bring me their heads, and I will receive them joyfully.’”

Failing to achieve an accord yet still forced to leave the chief’s territory to his rear, de Soto decided to safeguard his ships by garrisoning 120 men under the command of Pedro Calderon. With desertion an ever-present concern, de Soto sent the six larger ships away, leaving only a caravel and two brigantines in the harbor. He then began his march to the north.

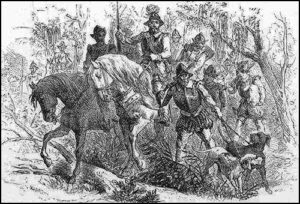

De Soto quickly learned of the difficult terrain and the Indians’ plan for dealing with him. Some accounts of the expedition state that the Spaniards faced annihilation, being frequently ambushed (particularly while bogged down traversing the vast swamps). In his book Hernando de Soto, historian Robert Graham describes this march: “Three days he and his men struggled along, their horses splashing in water to the girth, the infantry wading up to their knees and fighting every step. Three days of agony, of hunger, and of misery caused by the myriads of mosquitoes which filled the air; days of continuous fighting which almost maddened all his men.”

De Soto quickly learned of the difficult terrain and the Indians’ plan for dealing with him. Some accounts of the expedition state that the Spaniards faced annihilation, being frequently ambushed (particularly while bogged down traversing the vast swamps). In his book Hernando de Soto, historian Robert Graham describes this march: “Three days he and his men struggled along, their horses splashing in water to the girth, the infantry wading up to their knees and fighting every step. Three days of agony, of hunger, and of misery caused by the myriads of mosquitoes which filled the air; days of continuous fighting which almost maddened all his men.”

Those Indians that could be captured were put in chains and made bearers, thereby freeing other expedition members to fight. When de Soto found a village suitable for resting his men, they would occupy it. Though he believed this would provide safety from Indian ambushes, it was not to be: the Indians simply would retreat to the safety of the forest and plot other forms of ambush. Historian Graham’s translation again provides detail:

The Indians everyday attacked them, and so persistently that if a soldier strayed but one hundred paces from the camp an arrow pierced him, and before his comrades could run up, his head was severed from the trunk and borne off to the chief. The soldiers buried the bodies, and at night the Indians returned and dug them up, and hung them to the trees. During the twenty days they stopped to rest de Soto lost fourteen men.

De Soto’s men met brutality with brutality. When their Indian slaves revolted, many of the Spaniards, including de Soto, were injured. Once de Soto regained consciousness, he ordered a mass execution.

De Soto’s men met brutality with brutality. When their Indian slaves revolted, many of the Spaniards, including de Soto, were injured. Once de Soto regained consciousness, he ordered a mass execution.

When de Soto had sufficiently recovered, the march continued but their troubles only increased. They had entered the lands of the Muskegon tribes, and now de Soto (like Narvaez before him) was to learn just how fierce the Muskegons—”first-rate fighters”—could be.

Carrying bows which no Spaniard could so much as bend they shot with terrific force their crude but carefully constructed arrows. Some of these were tipped with fish bone, as sharp as a needle. Others had flint heads, many of which were serrated and caused ugly festering wounds. Generally, however, these would break when they struck upon armor. The most dangerous kind to the Spaniards, were the cane arrows that had been pointed and hardened in the fire. These would split against iron, and the splinters find their way between the gaps in chain-mail.

Garcilaso de la Vega later recorded that these Indians wasted little time in reminding the Spaniards of their history.

The Indians increased their attacks on all sides, anxious now to break and destroy them. Moreover, they gathered new strength and spirit in recalling that it had been in this identical swamp, although not the same pass, that ten or eleven years previously they had routed and destroyed Pamphilo de Narvaez; and they at this time reminded the General and his men of their previous deed, adding among other impertinent remarks and affronts that they would do the same with their present foes.

From the account of the “Gentleman of Elvas” this information was not well received:

There whole company was verie sad for these newes; and counseled the governor to goe back to the port de Spirito Santo, to abandon the countrie of Florida, lest he should perish as Narvaez had done: declaring that if he went forward, he could not return backe when he would, and that the Indians would gather up that small quantite of maiz which was left. Whereunto the Governor answered, that he would not goe backe, till he had seene with his eies that which these reported: saying that he could not believe it, and that we should be put out of doubt before it were long and he sent to Luys de Moscoso, to come presently from Cale, and that he tarried for him, heere.

With the approach of winter, de Soto and the main force of the company found suitable quarters in a village named Anhaica, some eight leagues from the sea and even closer to the village Narvaez’ Spaniards had occupied 12 years earlier. Once Anhaica was secured, de Soto sent a party of men to explore the coast for a suitable bay or inlet where he could bring up his ships from Espiritu Santo. They succeeded, finding the same bay where Narvaez’ men had built small boats in their desperate attempt at escape. They found the graves, the skulls of butchered horses, remnants of a forge and other discarded tools and materials. And Garcilosa de la Vega describes this search for a message: “Captain Juan de Anasco and his soldiers searched in the hollows and under the bark of trees to ascertain if letters had been left which would disclose what their predecessors had seen and noted, it being a very usual custom for the discoverers of new lands to leave such announcements for those to come.”

With the approach of winter, de Soto and the main force of the company found suitable quarters in a village named Anhaica, some eight leagues from the sea and even closer to the village Narvaez’ Spaniards had occupied 12 years earlier. Once Anhaica was secured, de Soto sent a party of men to explore the coast for a suitable bay or inlet where he could bring up his ships from Espiritu Santo. They succeeded, finding the same bay where Narvaez’ men had built small boats in their desperate attempt at escape. They found the graves, the skulls of butchered horses, remnants of a forge and other discarded tools and materials. And Garcilosa de la Vega describes this search for a message: “Captain Juan de Anasco and his soldiers searched in the hollows and under the bark of trees to ascertain if letters had been left which would disclose what their predecessors had seen and noted, it being a very usual custom for the discoverers of new lands to leave such announcements for those to come.”

On or near November 17, 1539, Anasco’s scouting party returned to Anhaica and gave word of their find. The discovery, historian Theodore Maynard stated,

shattered the morale of the army. This would be their fate too. Why should they fare better than Narvaez? He had been a stout captain, but he had perished and all his men with him. De Soto was implored to turn back.

De Soto told his men that if they “thought that they were in the position of Narvaez, let them do what Narvaez had done and build boats and suffer his fate.” Anasco was then ordered to bring up the ships with Calderon and his men. With that done, the brigantines set sail for Cuba and the caravel under command of Maldonado was ordered to explore the coast farther west. The expedition was thereby stranded in the lands of the Muskegon, where Maynard writes,

the Spaniards, though spared the fatigues of the march, were incessantly beset by the savages. Twice their encampment was set on fire, and it was always unsafe for any small body of men to go far from the settlement. The Indians made light account of the drastic penalties they received when caught. And as death had no terrors for them their noses and hands were cut off. But … their ferocity actually seemed to increase as consequence of such measures.

Theodore Irving’s translations of The Florida of the Inca as well as the Relacam Verdadeira adds further detail: the Indians “never pretended to oppose any body of soldiers drawn up in squadron, but roved in bands about the forest to surprise foraging parties, or lurked about among thickets to cut off any stragglers from the camp.” During that winter de Soto lost 20 soldiers and the area surrounding the Anhaica became so dangerous that few ventured any distance “unless well-armed and in strong parties.”

Theodore Irving’s translations of The Florida of the Inca as well as the Relacam Verdadeira adds further detail: the Indians “never pretended to oppose any body of soldiers drawn up in squadron, but roved in bands about the forest to surprise foraging parties, or lurked about among thickets to cut off any stragglers from the camp.” During that winter de Soto lost 20 soldiers and the area surrounding the Anhaica became so dangerous that few ventured any distance “unless well-armed and in strong parties.”

Clearly, de Soto’s men had cause to view their future with anxiety. They were caught in a war they could not win in a land they could not leave. Naturally, the idea of desertion occurred, and opportunity abounded. De Soto repeatedly sent out strong detachments on reconnaissance patrols that could take seven to 10 days, often going as far as 40 or 50 miles. Indeed, the Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission confirms desertion as a problem: “On several occasions we are told that a subordinate officer coming into camp with men missing was soundly berated and dispatched in haste to recover them.”

By the summer of 1540, desertion was no longer merely a problem but a paramount concern. De Soto’s ships had, by then, arrived at a previously arranged rendezvous point, yet de Soto “found reasons for not informing his subordinate [Maldonado] that he was near at hand.” Their rendezvous was delayed for several months.

Despite the Spaniards’ difficulties, why would a small number of men attempt a 3,000-mile crossing of unexplored frontier, and to what end? Wouldn’t the obstacles appear insurmountable? What provisions could they possibly take that would keep them alive while crossing a wilderness so foreign and diverse? How could they hope to prevail against the many hostile Indians they could expect to encounter? And yet, fear and desperation have been known to prompt irrational acts that are not always as irrational as they first appear.

The Spanish explorers were quite adept at their trade and a large part of that trade was simply surviving. When Coronado began his return to Mexico in 1542, he left friars Juan de la Cruz and Juan de Padilla, aide Andres de Campo and other attendants in the Kansas region. After friar Cruz was martyred by Indians, the others set out to return to Mexico. Several actually survived, finding their way back to Mexico some 10 years later.

Similarly, a Spanish pilot for Drake named Morera was put ashore on the California coast not long after falling ill. Once abandoned, he apparently made a swift recovery and after four years managed to reach the Spanish port of Culiacan on the west coast of Mexico. Another account involves John Hawkins’ men: of the 20 put ashore on the northern stretch of the Mexican Gulf coast during 1568, David Ingram, Richard Browne and Richard Twide later claimed to have survived a journey that took them in one year from Mexico to Nova Scotia.

Similarly, a Spanish pilot for Drake named Morera was put ashore on the California coast not long after falling ill. Once abandoned, he apparently made a swift recovery and after four years managed to reach the Spanish port of Culiacan on the west coast of Mexico. Another account involves John Hawkins’ men: of the 20 put ashore on the northern stretch of the Mexican Gulf coast during 1568, David Ingram, Richard Browne and Richard Twide later claimed to have survived a journey that took them in one year from Mexico to Nova Scotia.

Though doubts linger regarding the Ingram journey, the accounts of Morera and the Coronado party are verified. Still, these men literally were forced by circumstance to make their journeys, which does not explain why 13 men would leave the relative safety and provisions of de Soto’s party.

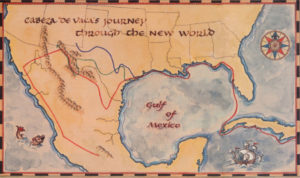

Perhaps they found precedent and inspiration in the narrative of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca—an officer in the Narvaez expedition that had landed in Florida 12 years before de Soto’s. Out of a force of roughly 300 men, Nunez was one of only four who survived. After his return to Spain, Nuñez recounted how for six years they had lived as the Indians’ captives before discovering a way to survive an overland journey to Mexico.

On an island of which I have spoken, they wished to make us physicians without examination or inquiring for diplomas…. They ordered that we also should do this and be of use to them in some way. We laughed at what they did, telling them it was folly, that we knew not how to heal. In consequence, they withheld food from us until we should practice what they required. Seeing our persistence, an Indian told me I knew not what I uttered, saying…certainly that we who were extraordinary men must possess power and efficacy over all other things. In his [God’s] clemency he willed that all those for whom we supplicated, should tell the others that they were sound and in health, directly after we make the sign of the blessed cross over them. For this the Indians treated us kindly; they deprived themselves food that they might give to us, and presented us with skins and some trifles.

As many illnesses were functional, Nuñez and the others had remarkable success with their technique. When they finally made their escape by traveling west, word of their medicine powers preceded them and their arrival at villages was eagerly anticipated. Greeted with enthusiasm measured in reverence, generosity and great rejoicing, the Spaniards responded by freely administering their healing.

As many illnesses were functional, Nuñez and the others had remarkable success with their technique. When they finally made their escape by traveling west, word of their medicine powers preceded them and their arrival at villages was eagerly anticipated. Greeted with enthusiasm measured in reverence, generosity and great rejoicing, the Spaniards responded by freely administering their healing.

All who heard it came to us that we might cure them and bless their children, and when the Indians in our company had to return to their country, before parting they offered us all the tunas they had for the journey, not keeping a single one, and gave us flint stones as long as one and a half palms, with which they cut and that are greatly prized among them so they left, the happiest people upon earth, having given us the very best they had. During that time they came for us from many places and said that verily we were children of the sun.

Whenever Nunez and the others sought to continue traveling, the Indians would guide the Spaniards in the direction they wished to go. For two years following their escape, the party meandered west in the company of many different tribes.

Nuñez’s record of their arrival in Mexico contrasts the influence of their wilderness experience with the reality of Spanish colonialism. In many ways, they had become the men the Indians believed them to be.

They were willing to do nothing until they had gone with us and delivered us into the hands of other Indians, as had been the custom; for if they returned without doing so, they were afraid they should die, and going with us, they feared neither Christians nor lances. Our countrymen became jealous at this, and caused their interpreter to tell the Indians that we were of them, and for a long time we had been lost; that they were the lords of the land who must be obeyed and served, while we were persons of mean condition and small force. The Indians cared little or nothing for what was told them; and conversing among themselves said the Christians lied: that we had come whence the sun rises, and they whence it goes down: we healed the sick, they killed the sound; that we had come naked and barefooted, while they had arrived in clothing and on horses with lances; that we were not covetous of anything, but all that was given to us, we directly turned to give, remaining with nothing; that the others had the only purpose to rob whomsoever they found, bestowing nothing on anyone.

They were willing to do nothing until they had gone with us and delivered us into the hands of other Indians, as had been the custom; for if they returned without doing so, they were afraid they should die, and going with us, they feared neither Christians nor lances. Our countrymen became jealous at this, and caused their interpreter to tell the Indians that we were of them, and for a long time we had been lost; that they were the lords of the land who must be obeyed and served, while we were persons of mean condition and small force. The Indians cared little or nothing for what was told them; and conversing among themselves said the Christians lied: that we had come whence the sun rises, and they whence it goes down: we healed the sick, they killed the sound; that we had come naked and barefooted, while they had arrived in clothing and on horses with lances; that we were not covetous of anything, but all that was given to us, we directly turned to give, remaining with nothing; that the others had the only purpose to rob whomsoever they found, bestowing nothing on anyone.

Thereupon we had many and bitter quarrels with the Christians, for they wanted to make slaves of our Indians.

Thus, the survivors reached the Spanish settlement of Culiacan eight years after their arrival in Florida and without aid of European technology. The journey completed three years before de Soto’s landing in Florida. Moreover, their story would have been well known to the soldiers in de Soto’s command. Indeed, Nuñez had turned down a commission offered by de Soto.

The foregoing accounts do provide a context supporting both a plausible motive as well as the feasibility of a journey such as that described in the Oroville newspaper article. Offering further support is a thoroughly documented account suggesting the presence of Spanish soldiers in Alta California in 1542—only 50 years after Columbus, more than 200 years before the establishment of the first Alta California mission and corresponding with the date given in the Oroville Mercury article.

The foregoing accounts do provide a context supporting both a plausible motive as well as the feasibility of a journey such as that described in the Oroville newspaper article. Offering further support is a thoroughly documented account suggesting the presence of Spanish soldiers in Alta California in 1542—only 50 years after Columbus, more than 200 years before the establishment of the first Alta California mission and corresponding with the date given in the Oroville Mercury article.

The journal of Rodriguez Cabrillo—his log of the voyage—is marked by numerous reports of Spaniards moving about the Alta California interior. The farther Cabrillo sailed, the more often he wrote of bearded men dressed in Spanish clothing going about the inland country. For example, the following entry is dated Saturday, October 3, 1542 and made at approximately 300 north latitude [off Baja California]:

After anchoring they went ashore where there were some people, three of whom awaiting them, while the rest fled. To these some presents were given, and they explained by signs that inland people like the Spaniards had passed…. The following day in the morning three large Indians came to the ships and explained by signs that some people like us, that is, bearded, dressed and armed like those on board the vessels, were going about inland. They showed by signs that these carried cross-bows and swords; they made gestures with the right arm as if using lances, and went running about as if they were going on horseback, and further showed that these were killing many of the native Indians, and for this reason they were afraid.

Much farther along the coast, the ships arrived at the Santa Barbara Channel Islands and again they heard reports “that men like the Spaniards, wearing clothing and having beards, were going around on the mainland.”

The following day the ships arrived near the mainland of what is now believed to have been San Pedro Bay where, Cabrillo recorded,

they engaged in intercourse with some Indians they captured in a canoe, who made signs to them that towards the north there were Spaniards like them.

they engaged in intercourse with some Indians they captured in a canoe, who made signs to them that towards the north there were Spaniards like them.

After traveling two more days—about 36 miles further north—the Indians no longer displayed fear of the Spaniards but came to greet them instead.

We saw on land an Indian town close to the sea with large houses like those of New Spain, and they anchored in front of a large valley on the coast. Here many fine canoes holding twelve or thirteen Indians each came to the ships, and gave news of Christians who were going about inland. The coast runs northwest-southeast…. They made signs that in seven days one could go to where the Spaniards were, so Juan Rodriguez decided to send on a chance two Spaniards inland with these Indians with a letter to the Christians. They explained besides that there was a large river. The town is 35 0 20′ [near San Luis Obispo]. The country within is a beautiful valley, and the Indians explained that inland in that valley there was much maize and food. Beyond this valley some high, very broken sierras were visible. They call the Christians Taquimine.

Sailing still farther up the coast, they were frequently visited by Indians who paddled their canoes alongside the ships.

They are in a good country with fine plains and many trees and savannas. The people go about dressed in skins and say that inland at three days distance there are many towns and much maize. They call maize oep, and cows, of which they say there are many, they call cae. They also gave us news of people bearded and wearing clothes.

During the first week of November (somewhere in the vicinity of San Luis), Rodriguez Cabrillo made his last report referring to these Christians in the interior:

They wear skins of many different animals, eat acorns and a white seed the size of maize, which is used to make tamales. They live well. They say that inland there is much maize and men like us go about there.

Bad weather forced the ships to stay off shore and Rodriguez Cabrillo’s unexpected death ended the pursuit of the Christians. Their origin and identity would remain unknown.

Though there are no records of Spanish expeditions in Alta California during 1542, it’s conceivable that these reports referred to the expeditions of Alarcon or Diaz, both of which traversed the lower Colorado River region in the years preceding 1542. Because Diaz’ party contained both horses and dogs, his expedition might well explain those first reports as well as the Indians’ reference to a large river. But both the Alarcon and Diaz journeys ended in 1540, two years before Rodriguez Cabrillo’s northerly positions. Also, the journey from the lower Colorado to the locations of the interior Christians would require more than three or seven days, especially at the end of the dry season.

Though there are no records of Spanish expeditions in Alta California during 1542, it’s conceivable that these reports referred to the expeditions of Alarcon or Diaz, both of which traversed the lower Colorado River region in the years preceding 1542. Because Diaz’ party contained both horses and dogs, his expedition might well explain those first reports as well as the Indians’ reference to a large river. But both the Alarcon and Diaz journeys ended in 1540, two years before Rodriguez Cabrillo’s northerly positions. Also, the journey from the lower Colorado to the locations of the interior Christians would require more than three or seven days, especially at the end of the dry season.

Then too there was Coronado’s journey through western Mexico and the Yuman Indian territories, concluded early in 1542. Because the first report occurred in Yuman or southern Shoshonean territory, there is a possible chain of communication regarding the presence of the Coronado party. Ordinary delays in communication may have led them to believe that Coronado was nearer at hand.

But again, the problem is that the later reports of inland Christians occurred much farther north, in Chumash territories where they already had a name for Europeans, “Taquimine.” Moreover, the Northern Chumash’s primary trade contacts seem to have been with the Southern Valley Yokut. Amongst the Yokut, the tribal name “Tachi” was prominent, and linguistically this English spelling of the word seems very close to the “Taqui” segment of the word the Chumash used for Christians apparently separated only by phonetic differences of Spanish notation. Also of interest is that California Indian anthropologist Alfred Kroeber noted that the Chumash referred to the Yokuts (the Indians of the San Joaquin Valley) as “Chminimolich” or “Northerners” and that fully half of the Yokut’s tribal names end in some facsimile of -imni. Further, the Chumash’s northeastern territory was bordered by the Tachi Yokut. Now whether the Chumash would have identified the Europeans by using a Yokut word or place name cannot be determined, but it remains a distinct possibility.

Cabrillo’s reference to maize presents another question. At that time, Native Americans cultivated corn in the Colorado basin but not in the San Joaquin Valley. Yet the Chumash told Cabrillo that maize was grown within that “very beautiful” valley west of the “high sierras” and but three day’s journey inland, where cows could also be found. At that time, the San Joaquin Valley would have been rich in game such as antelope, deer and perhaps elk, but domesticated cattle were unknown to the Chumash (though, given the extensive trade relationships between Indian peoples, the Chumash may have known of the closest thing to a cow, the buffalo). Finally, both Spaniards and Chumash would distinguish north from south similarly. Though the southern tribes may have been referring to Coronado or one of the other earlier expeditions, other evidence strongly indicates that the Chumash were talking about an area farther north.

Supporting the idea that the Indians used the place names and knew the locations of other distant tribes is Zarate Salmeron’s record of Juan de Onate’s expedition of 1595, which traveled west of the Colorado River and some five leagues into California. One tribe (probably Shoshonean), on seeing the Spaniards, tied crosses to a lock of hair falling on their foreheads. These Indians, who had made contact with unknown Europeans “many years” earlier, also referred to a distant tribe located at the western sea some 20 days’ journey away. Zarate Salmeron states that, “They also said that two days’ journey from there was a river of little water, by which they went to another very large one that enters into the sea, on whose banks there was a nation called Amacava.”

Supporting the idea that the Indians used the place names and knew the locations of other distant tribes is Zarate Salmeron’s record of Juan de Onate’s expedition of 1595, which traveled west of the Colorado River and some five leagues into California. One tribe (probably Shoshonean), on seeing the Spaniards, tied crosses to a lock of hair falling on their foreheads. These Indians, who had made contact with unknown Europeans “many years” earlier, also referred to a distant tribe located at the western sea some 20 days’ journey away. Zarate Salmeron states that, “They also said that two days’ journey from there was a river of little water, by which they went to another very large one that enters into the sea, on whose banks there was a nation called Amacava.”

The word “Anacapa” is a Chumash place name. The similarity of the two words seems to indicate a working knowledge of Chumash locations as well as the travel times involved.

Although no evidence decisively connects 16th-century Spaniards with the Feather River region, two records specifically refer to a latent Caucasian strain within one of the Feather River tribes. These references, undocumented, first appear in turn-of-the-century biographic notes discussing the historical notoriety of a Maidu chief: “His features were those of the white man’s—prominent Roman nose but hair and complexion that of the Indian.”

A kind of a royal family seems to have existed in this tribe, and the captain belonged to this family; and it was generally believed that white blood flowed in his veins, but of this no information could be obtained from the tribe.

T his c.1850s reference, in mentioning an extended “family” characteristic, implies that such a white strain would have been introduced several generations earlier—an idea strongly supported by other unique elements of culture specific to the Feather River. First is their distinctive method of identifying village territories, as anthropologist Roland Dixon describes:

his c.1850s reference, in mentioning an extended “family” characteristic, implies that such a white strain would have been introduced several generations earlier—an idea strongly supported by other unique elements of culture specific to the Feather River. First is their distinctive method of identifying village territories, as anthropologist Roland Dixon describes:

The whole area occupied by this group of four “tribes” was divided by boundary lines, each section forming a rude square, the corners being marked by the designs of the abutting tribes…. The lines connecting these corners were carefully determined, and remembered with exactness.

Alfred Kroeber believed this method imitated white surveying practices, yet Dixon’s research involved traditions established before the coming of the whites. The practice was unknown elsewhere among the Maidu or other California tribes. Kroeber may have also taken into account the symbols used: three vertical lines for the Oroville peoples, a “Latin” cross for the Bidwell Bar region, an upturned crescent for the Bald Rock people and three vertical lines and a Latin cross for the Mooretown villages.

Another anthropological record relates a legend also unique to the region, told to A.G. Fassin by Tome Ya Nem during the interview later titled “The Concow Indians” and published in The Overland Monthly during 1884:

This is the story of our race, as brought forward and told to us….by the old men, the scholars and the priests of our tribe.

Wahno-no-pem [the Great Spirit, caused Yane-ka-num-ka-la, the White Spirit, to appear in the flesh unto the people, that he might enlighten and turn them from their evil ways; and this good man began his teachings at Wel-lu-da, where the white face has since built his home, and which he calls Chico. For many years he lived among our people, teaching the young men and the maidens many lessons of love and wisdom, many songs and games and gentle pastimes; and in all these years they loved him more and more. But he died, and the lessons were forgotten; the songs died away in the forests, and in their stead came the war-whoop, the shrieks of struggling women, and the groans of the wounded and the dying; and the name of Yane-ka-num-ka-la became a jibe and a mockery all over the land.

This isolated reference to the arrival of a man” who was the “White Spirit” appearing “in the flesh” is exclusive to the Concow. Also worth noting is the assertion that he lived out the remainder of his life influencing the culture of these peoples yet dying as an ordinary man.

A neighboring tribe known as the Yana also had peculiar mysteries attached to it. Steven Powers, who conducted his work amongst the California tribes in the 1870s, deemed it necessary to preface his Yana notes by stating that they were “so early civilized, and are so nearly extinct, it is not easy to learn much concerning their aboriginal usages.”

The principal interest attaching to them is the question of their origin. There is an ancient tradition…. that their ancestors came from a country very far toward the rising sun. They journeyed a great many moons, crossing forests, prairies, mountains, plains, deserts, and rivers so great, according to their description, that they could have been found nowhere except in the interior of the continent. At length they came to a delightful and to a timid and feeble folk, where they conquered for themselves a dwelling-place, and rested therein.

Powers noted another interesting detail, perhaps as a possible corroborative detail supporting the migration reference:

The narrator of the story states that Major Reading once showed him an old flint-lock musket which he had found in possession of the Nozi [Yana], and which had been so worn by being loaded with gravel that it was as thin as paper at the muzzle. It was not known how they could have obtained it, unless they had brought it with them from the Atlantic States.

The narrator of the story states that Major Reading once showed him an old flint-lock musket which he had found in possession of the Nozi [Yana], and which had been so worn by being loaded with gravel that it was as thin as paper at the muzzle. It was not known how they could have obtained it, unless they had brought it with them from the Atlantic States.

Noting distinct linguistic differences, the modern anthropologist Robert Heizer criticizes Powers for believing this story. Yet the mention of a flint-lock is intriguing, and provides context to an artifact presumably dating from the early 17th century as the Spanish Arquebus used a smoldering cord rather than a flint. Nevertheless, the flintlock record remains little more than hearsay considering that much of Powers’ information was derived through a third party.

To the traditional historian, this effort to identify various elements of Indian culture as possible influences from a prehistoric Spanish contact is tenuous at best. Yet because the Maidu or Yana lacked a written language, such contact only could survive as oral tradition taking on the quality, over time, of either legend or unique cultural practices. Much modern analysis of Native Californian culture is, in the final analysis, little more than educated guesswork based on rudimentary records dating from the embryonic stages of Indian ethnology and anthropology.

One additional piece of documentation solidly supports the suggestion of an early Spanish presence in the Maidu and Yana regions: the text transcription of an interview conducted in 1956, recording the 1932 recovery of Spanish armor from a cave on Deer Creek, north of the Feather River. Deer Creek was a northern territorial border separating the Concow and the Yahi (a southern division of the Yana). Subsequent interviews with the same man were conducted decades later, during 1978 and 1991. The informant—now in his eighties has denied contributing to the 1956 document or previously speaking of the incident outside of his immediate family. He also pointed out that several details were in error.

As the story now stands corrected, the informant and two of his friends were present at the opening of a semi-sealed cave during a summer fishing trip sometime between 1930 and 1932. They had been asked to help a “professor” who had approached them while they were fishing at the creek. On entering the cave, the first objects the informant and his companions saw were a piece of rusted chest armor leaning against the cave wall laying alongside a curved, grooved helmet. A few feet away was a pointed axe head with a curved blade that looked as though it might have been attached to a staff. The old man mentioned that the cave appeared to have been used for shelter as it contained stones arranged for a fire. He stated that the professor, upon seeing the armor, blurted out that it didn’t belong there, that it was from Cortes’ era. Beyond those details, the informant said he recalled only that the artifacts were going to be taken to the “California Museum.” (The author’s efforts to locate these artifacts have proved fruitless.) When questioned, the informant knew nothing else: he could not place the event into a greater context and was not familiar with the Oroville Mercury article.

As the story now stands corrected, the informant and two of his friends were present at the opening of a semi-sealed cave during a summer fishing trip sometime between 1930 and 1932. They had been asked to help a “professor” who had approached them while they were fishing at the creek. On entering the cave, the first objects the informant and his companions saw were a piece of rusted chest armor leaning against the cave wall laying alongside a curved, grooved helmet. A few feet away was a pointed axe head with a curved blade that looked as though it might have been attached to a staff. The old man mentioned that the cave appeared to have been used for shelter as it contained stones arranged for a fire. He stated that the professor, upon seeing the armor, blurted out that it didn’t belong there, that it was from Cortes’ era. Beyond those details, the informant said he recalled only that the artifacts were going to be taken to the “California Museum.” (The author’s efforts to locate these artifacts have proved fruitless.) When questioned, the informant knew nothing else: he could not place the event into a greater context and was not familiar with the Oroville Mercury article.

Regarding the “professor,” the informant first recalled that he had been wearing a dusty suit coat, but no shirt, and his pants were wet to the waist with the cuffs rolled up. The old man’s most significant memory was that the professor’s glasses were the old-fashioned wire-rimmed grandpa-type and that the man had a peculiar smile. During the 1991 interviews, the informant further recalled that the professor also had worn a wide, flat-brimmed hat, a dark full beard, and was a forceful walker. Finally, the informant said that this man had been part of a small group the informant thought was from Stanford University.

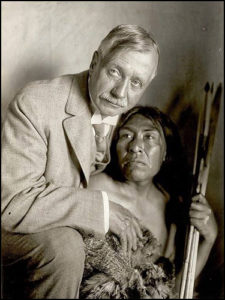

It is possible that the mysterious “professor” was John Peabody Harrington, who was conducting field work on Deer Creek during those years. Though most linguists or ethnologists of his stature would have lost no time publishing such a find as 16th-century Spanish armor, Harrington was different. Very secretive about his fieldwork, Harrington often concealed it not only from California linguist Alfred Kroeber (who did more compiling of others’ work than working in the field) but also from his superiors at the Smithsonian, perhaps out of fear of premature publication. Harrington, a perfectionist, believed in erring on the side of thoroughness and, unlike Kroeber, was almost totally devoid of hunger for professional acclaim. He wanted to get it right.

It is possible that the mysterious “professor” was John Peabody Harrington, who was conducting field work on Deer Creek during those years. Though most linguists or ethnologists of his stature would have lost no time publishing such a find as 16th-century Spanish armor, Harrington was different. Very secretive about his fieldwork, Harrington often concealed it not only from California linguist Alfred Kroeber (who did more compiling of others’ work than working in the field) but also from his superiors at the Smithsonian, perhaps out of fear of premature publication. Harrington, a perfectionist, believed in erring on the side of thoroughness and, unlike Kroeber, was almost totally devoid of hunger for professional acclaim. He wanted to get it right.

Harrington was also known for his eccentric field dress, often wearing a suit with no shirt, for example. He also wore peculiar wire rimmed glasses and frequently elicited the aid of young apprentices in performing his fieldwork. He was quite well versed in 16th-century Spanish exploration and had written a related article for The Pan American Magazine in 1930. Lastly, he had attended Stanford University.

At odds with this conclusion is the mention of a full beard and wide brimmed hat, neither of which Harrington wore. Finally, there are no references to the recovery of Spanish armor in what has been published of his field notes (though much of his work has not yet been published) and other than Harrington’s, there is no record of fieldwork conducted on that section of Deer Creek during the years 1930 to 1932. The “professor” may well have been nothing more than a “pot hunter.”

Other than my own research, the late William H. Hutchinson is the only historian who has addressed the Mercury article. Titled “The Oroville Hoax,” Hutchinson’s informal critique challenges the newspaper’s credibility. He states that the article is the only reference to the event. He questions the miners’ use of oak to build a cabin, Castronjo’s wandering into the miners’ camp and the editor running across the Spaniard. And how, Hutchinson asks, could the parchment survive so long sealed in the cavity of an oak tree? Finally, he suggests that the story made for good filler on a day when advertising sales were down, adding that Señor Castronjo quite likely discarded the parchment soon after discovering he had been the victim of the two miners’ fraud.

It is hard to say why neither Hutchinson nor any other historian made a more methodological, serious inquiry than the foregoing—more an amusing piece of case-building rhetoric than analysis. Though each of Hutchinson’s criticisms raise a valid question, his interpretation lacks balance. For example, oak is a more difficult wood to work than pine, yet after 30 years of extensive, makeshift mining enterprises (along with a burgeoning lumber industry), there would have been few pines mill-worthy left standing on the lower Middle Fork. Further, oak is more common to the region. Hutchinson’s dismissal of the editor’s encounter with Castronjo as an unlikely event does not consider the nature of how news travels on the frontier. By 1879, Oroville’s population had diminished and in such a played-out mining district, the local “word-of-mouth” network would have enthusiastically taken up the mysterious parchment. Moreover, the Mercury’s statement that the writer “ran across” the Spaniard while “in quest” of items is preceded by a description of the discovery—suggesting that the newspaper had prior knowledge of the miners’ find and, possibly, its sale.

It is hard to say why neither Hutchinson nor any other historian made a more methodological, serious inquiry than the foregoing—more an amusing piece of case-building rhetoric than analysis. Though each of Hutchinson’s criticisms raise a valid question, his interpretation lacks balance. For example, oak is a more difficult wood to work than pine, yet after 30 years of extensive, makeshift mining enterprises (along with a burgeoning lumber industry), there would have been few pines mill-worthy left standing on the lower Middle Fork. Further, oak is more common to the region. Hutchinson’s dismissal of the editor’s encounter with Castronjo as an unlikely event does not consider the nature of how news travels on the frontier. By 1879, Oroville’s population had diminished and in such a played-out mining district, the local “word-of-mouth” network would have enthusiastically taken up the mysterious parchment. Moreover, the Mercury’s statement that the writer “ran across” the Spaniard while “in quest” of items is preceded by a description of the discovery—suggesting that the newspaper had prior knowledge of the miners’ find and, possibly, its sale.

The frontier journalism of the Feather River region was seldom precise and the writer’s particular indifference to reporting the specifics of each event would seem the norm rather than the exception. If the story was fabricated to sell newspapers, it seems unlikely that the writer would print the name of each party involved—particularly if there were real people behind the names.

The 1880 census of Butte County lists a James Reynolds as a 62-year-old miner and resident of Mountain Springs in Oregon Township (the district in question). Among the J. McCartys appearing in the 1870 census, one is listed in Butte Township and another in Marysville.

Finally, the scoffed-at notion that an oak tree could function as a vault for some 337 years is not so incredible. Oaks frequently have sealed hollows at their center and some varieties common to that region live far longer than three centuries. What better environment for preservation than one both sealed and resinous?

Finally, the scoffed-at notion that an oak tree could function as a vault for some 337 years is not so incredible. Oaks frequently have sealed hollows at their center and some varieties common to that region live far longer than three centuries. What better environment for preservation than one both sealed and resinous?

More important is the factor overlooked by Hutchinson—Castronjo’s identification of the “hieroglyphics” as Spanish letters. Significantly, Castronjo specified that only the quality of his education enabled him to “decipher” the writing. Indeed, historians such as Ignacio Avellaneda generally agree that a high degree of education would prove essential to the task of identification, even for someone thoroughly literate in Spanish. But despite the quality of Castronjo’s education, it would be unlikely that he could have provided a precise translation because in Old Spanish usage and phrasings are of a somewhat different idiom. This could explain why the Mercury reported only those elements most easily identified and legible—i.e., dates and names—with the balance of the article stating only that Castronjo referred to the writing as a “condensed history” of the deserters’ “wanderings, trials and tribulations” as well as such obvious facts as the manuscript having been placed in the knothole of a tree.

Verifying the three Spanish names mentioned in the Oroville Mercury against the register of Soto expedition members could help solve this mystery. Unfortunately, the names are not listed there. This does not mean that those three Spaniards did not participate in the expedition, however. Different sources give different numbers, ranging from Garcilaso de la Vega’s 1000 to Rangel’s 570 (not counting the sailors, some of whom were stowaways). Even the catalogue does not account for those who joined the expedition during de Soto’s prolonged stay in Cuba. In short, the register is known to be incomplete and participants are still being discovered. Complicating the problem is that the newspaper writer appears to have corrupted the spellings of the Spanish names, rendering identification more difficult.

Verifying the three Spanish names mentioned in the Oroville Mercury against the register of Soto expedition members could help solve this mystery. Unfortunately, the names are not listed there. This does not mean that those three Spaniards did not participate in the expedition, however. Different sources give different numbers, ranging from Garcilaso de la Vega’s 1000 to Rangel’s 570 (not counting the sailors, some of whom were stowaways). Even the catalogue does not account for those who joined the expedition during de Soto’s prolonged stay in Cuba. In short, the register is known to be incomplete and participants are still being discovered. Complicating the problem is that the newspaper writer appears to have corrupted the spellings of the Spanish names, rendering identification more difficult.

Considering that those specifics that do appear in the article reflect a familiarity with not only the practices of Spanish explorers, but also a pertinent date in the de Soto expedition; it seems likely that if fraud was committed Castronjo would have been the only viable perpetrator and not the two miners as Hutchinson implied.

Without the parchment itself or other identifying artifact, it is impossible to verify the authenticity of the manuscript, however compelling the circumstantial evidence. Was the story a hoax designed to drum up a little frontier notoriety? Conceivably. To argue in the newspaper’s defense would be naive, but it is equally naive to draw conclusions based on anything less than a thorough and objective analysis.

It’s a disservice to history to discount possibility due to seeming improbability, particularly for the sake of expedience or amusement as both may come at the expense of truth. Certainly, the converging nature of the “circumstantial” evidence suggests that some element of truth is involved in the Mercury article, though many questions remain unanswered, or simply unanswerable.

It’s a disservice to history to discount possibility due to seeming improbability, particularly for the sake of expedience or amusement as both may come at the expense of truth. Certainly, the converging nature of the “circumstantial” evidence suggests that some element of truth is involved in the Mercury article, though many questions remain unanswered, or simply unanswerable.

Alas, history requires better evidence. Fourteen years of search requests to directors of every major archive in Spain resulted in no record of the parchment. What became of Senor Castronjo and the manuscript remains an enigma of early California history. Perhaps Alvar Nuñez best explains the uncertain disposition of events of life that fall outside of our control. Not long after his return to Spain, in an audience with the King, Nuñez offered this prefatory statement as context to his improbable experience:

Although ambition and love of action are common to all, as to the advantages that each may gain, there are great inequalities of fortune, the result not of conduct, but only accident, nor caused by the fault of any one, but coming in the providence of God and solely by His will. Hence to one arises deeds more signal than he thought to achieve; to another the opposite in every way occurs, so that he can show no higher proof of purpose than his effort, and at times even this is so concealed that it cannot of itself appear.